Computational simulation plays a crucial role in the management of natural hazards in Alpine environments, particularly rockfalls and avalanches. 3D models now make it possible to simulate the propagation of these mass movements, providing a better understanding of potential hazards and contributing to the implementation of effective preventive measures.

Can you tell us exactly what the 2D and 3D models mentioned in connection with the Blatten disaster consist of? What is it and for what purpose?

It’s important to note that Fugro was not involved in the modelling of the Blatten disaster, but the modelling approaches described here are consistent with those used in similar geohazard assessments.

The 2D and 3D models mentioned in the Blatten disaster refer to simulations used to understand and reconstruct the dynamics of debris flows or landslides over complex terrain.Predictive models for the propagation of mass movements vary significantly in complexity, both in their algorithmic approach and the accuracy of the physical models used to represent flow behaviour, or rheology. The basic dynamics are well understood: gravity drives the flow, while internal and basal friction resist it. But the way in which a mixture of rocks, sediments, ice, and water flows, like the Birch Glacier overlooking Blaten, is far more complex than that of, say, clear water released from a retention dam.

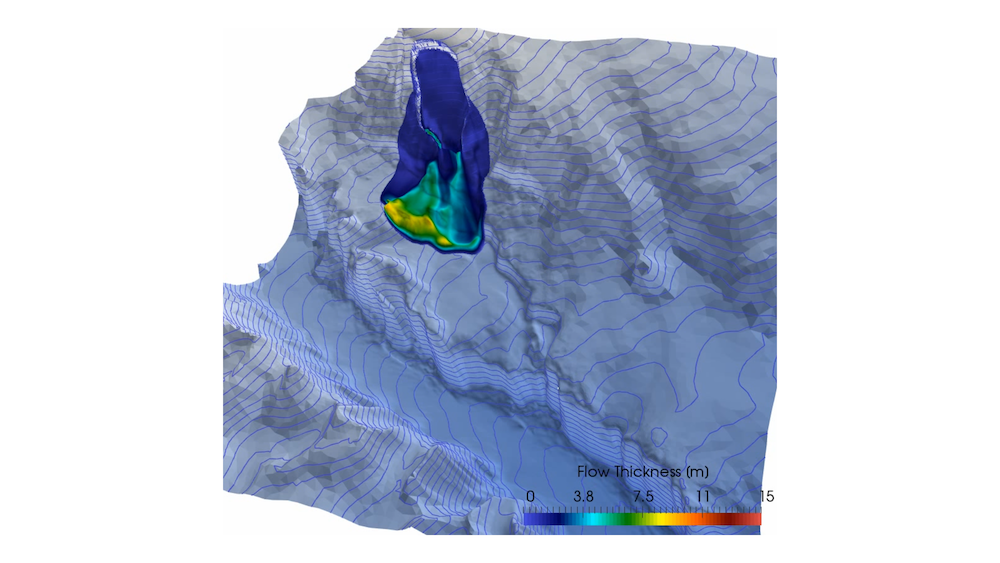

2D models are typically « depth-averaged » models, where flow thickness is (very) small compared to horizontal propagation, and all properties are averaged vertically. Historically, the main advantage of these models was their lower computational costs, enabling numerous simulations for sensitivity studies on uncertain parameters in risk assessment. This approximation’s accuracy depends on the specific case, but they are widely used and calibrated against numerous case studies to establish high and low range risk levels for a given environment.

3D models aim to resolve the complete vertical structure of the flow. They provide an algorithmic framework that better accounts for flow stratification, such as intense basal shear, and how different flow phases (solid, liquid, etc.) interact and react to this stratification. A wide range of 3D models were used in the Blatten disaster, including:

- Eulerian vision: a fixed-mesh, continuous ‘history’ approach

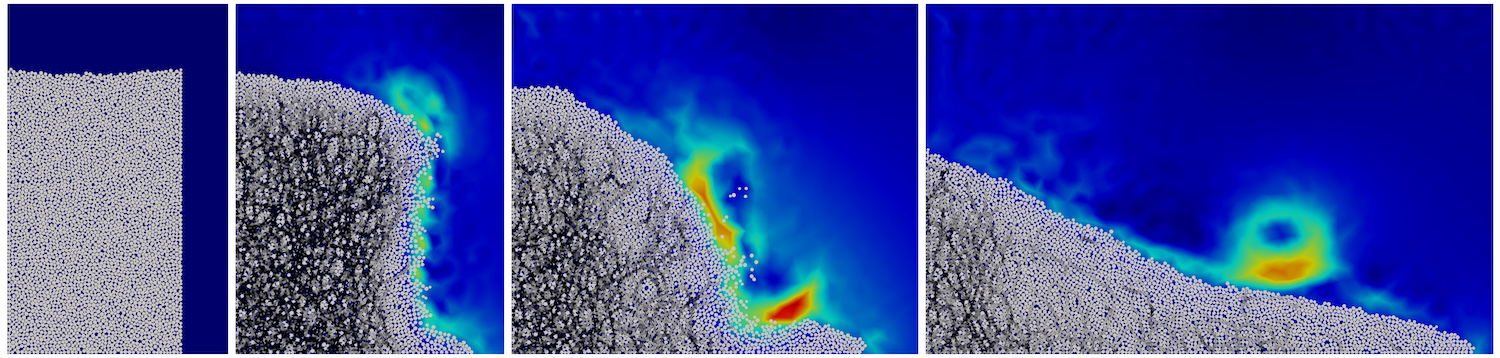

- Lagrangian approach: tracking the motion of pseudo-particles (e.g., the Material Point Method – MPM)

- Multiphase discrete element modelling (DEM-FEM), which, for the time being, remains confined to academic research (see figure granular column).

Over the last decade, advances in high-performance computing power and algorithms have made these 3D models operational for real-world case studies. While this may seem like a small revolution, it’s perhaps better described as an evolution. This development now allows us to largely overcome the « resolution complexity » of simulation and refocus, further upstream, on a better understanding of the natural environment’s complexity and its behavioural laws, which is precisely where major uncertainties and challenges of modelling still lie.

The use of simulation would significantly improve risk forecasting and management in Alpine environments: can you tell us more?

The growing range of digital modelling tools support the mapping and management of natural risks, particularly in Alpine environments, in a much more integrated manner, from a regional to a very local scale. Coupled with faster acquisition and processing of field data, as well as continuous monitoring, it makes it possible to build a true « digital twin » of the environment – a virtual replica that mirrors real-world conditions. This digital twin serves as a powerful decision-making and management tool for field stakeholders and authorities.

Can you explain at what point (in the natural risk) and based on what elements (data), experts can perform a digital simulation of a risk in an Alpine environment?

The link between data and simulation is crucial. A simulation model that isn’t given reliable input data will produce misleading or meaningless results. In the case of Blaten, continuous monitoring of the glacier since 1993 enabled experts to detect signs of increasing instability. This allowed them to anticipate the growing risk in the two weeks preceding the disaster, evacuate the village preventively, and limit the loss of life to a single casualty. The impact zone had been fairly accurately anticipated.

Less than three months later, however, a rockfall on the Chamonix road resulted in more fatalities. This emphasises the need for reliable geotechnical, geophysical, and hydrological data for the characterisation of the natural environment. Unlike other data, for example topographical, which can now be acquired quickly and accurately (using drones, satellite data, etc.), these often require more detailed investigation methods, sampling, laboratory tests, considering uncertainties, spatial variability, and the impact of climate change.

Advances in data science and their processing using advanced statistical methods are as important as those in numerical simulation itself. Taking uncertainties into account is a crucial element in risk management.

Given the increasing number of risks in the Alpine environment, do you think digital simulation could be a valuable ally? Can you cite other examples of natural hazards studied using digital simulation?

Digital simulation has reached a certain level of maturity, although it continues to be the subject of significant research. It is an essential tool in managing natural hazards within a given territory, allowing us to investigate the expected responses under changing conditions and across different scenarios, particularly with increased anthropogenic pressure and climate change.

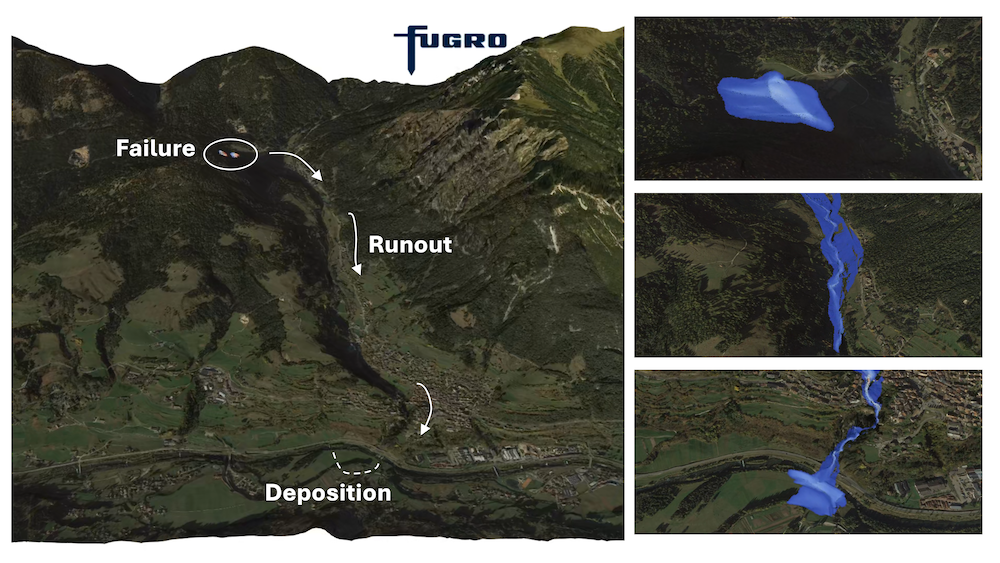

It is also one of the components in developing a digital twin. In our work, we apply similar simulation tools, coupled with data acquisition, to other types of natural hazards, such as the failure of mountain dams or mining dams (see Figure of the reconstruction of the Stava disaster, Italy), flash floods, debris flows, liquefaction risk, or even, in marine environments, the modelling of submarine landslides (see figure of submarine landslide),induced tsunamis, or turbidity currents.

About the Author

Benoit Spinewine is a civil engineer from UCLouvain, Belgium. His doctoral thesis focused on modelling the sedimentary impacts (erosion, transport, deposition) of extreme floods, such as those caused by dam or levee failures.

He currently leads the « Dynamic Modelling » consulting division at Fugro, the world’s leading Geo-data specialist. His team specialises in the characterisation of natural hazards, both in coastal and marine environments and on land.

In addition to his role at Fugro, he is a lecturer at UCLouvain and is actively involved in two European research projects related to this topic.